When Less is More: A Tale of Two Bats

Author's note: A version of this post originally appeared on my old site, The Ink and Pixel Club.

Author's note: A version of this post originally appeared on my old site, The Ink and Pixel Club.

Comparing two works based on the same source material can lead to interesting discoveries. Seeing how the same story is handled can reveal the differences in the filmmakers and their approaches to their craft. If can highlight the strengths and weaknesses of different media. Or, as with the two works we’re going to look at today, it can reveal a much broader concept, like the positive side of limitations.

Batman is an ideal subject for this kind of comparison. DC’s dark knight has been repeatedly reinterpreted for different media, different audiences, and different times. Yet in nearly every new version, a few key elements remain the same, keeping the result recognizably Batman. The part of the Batman mythos that we’ll be examining today is the death of the Graysons, a key moment in the origin of Batman’s sidekick, Robin.

Let’s start out with Joel Schumacher’s 1995 film Batman Forever. (Oh stop groaning. It’s not like I’m making you watch Batman and Robin.) For fans of Tim Burton’s moody, gothic take on wealth playboy Bruce Wayne and his masked alter ego, this film was a marked departure from what had come before and the beginning of a sharp downturn in quality for the Batman films. Batman Forever draws influence from both the Burton films and the campy 1960s TV series, two takes on the character which never quite join into a cohesive whole. Plotwise, the movie is tasked with introducing audiences to two new villains, one new Bat babe*, numerous incidental characters, and one new hero.

In the scene we're interested in, Bruce Wayne has taken the lovely Dr. Chase Meridian to the circus. Two-Face (played here by Tommy Lee Jones, who seems to have left his considerable acting talent in his other pants) takes the whole big top homage and threatens to detonate a large bomb. Watching from high above are the Flying Graysons, a family of talented trapeze artists consisting of a husband and wife, their younger son Dick, and an older son who I don’t believe has any precedent in the comics. The Graysons form a plan to stop the bomb, now suspended high above the center ring. Dick climbs up to the scaffolding at the top of the building while his parents and brother climb out onto the rigging to try to reach the bomb.

The death of the Graysons plays out as follows. Two-Face shoots down the rigging that Dick’s family is clinging to. Dick Grayson, unable to see what is happening, grabs the bomb and pushes it off the roof into a nearby body of water while his family plummets helplessly to the floor below. Two-Face escapes through a convenient trap door in the floor. The camera cuts from the falling Graysons to a point of view shot of the bullseye-like design of the center ring drawing rapidly closer, and finally to the horrified and stunned reactions of first Dr. Meridian, then Bruce Wayne. There is no sound to indicate the end of the Graysons’ fatal fall, only a swell in the music.

The camera looks down from far above at the lifeless bodies of the three Graysons. Seconds later, the one surviving Grayson looks down at the same grisly tableau. Bruce Wayne looks up to see a shocked and grief-stricken Dick Grayson discovering the death of his family, a feeling that Bruce can well understand.

Now on to the fun part. We’re going to see the same story – with a couple of significant details changed – as depicted in Batman: The Animated Series. This groundbreaking TV show is both an undisputed classic and personal favorite. If you talk to me about Batman without any specific context, this is what I think of by default. The show’s streamlined, graphic approach to character design and sophisticated writing paved the way for not only future Warner Brothers shows set in the DC Comics universe, but also an explosion of superhero series that continues to this day. Batman: TAS is the granddaddy of them all and the standard by which the newcomers are measured.

The animated series covers Robin's origin in the two-part episode "Robin's Reckoning." The events that lead up to death of the Graysons begin about eight minutes into part one.

The back story of the Flying Graysons remains much they same. They are a happy, loving family of trapeze artists, though in this version, Dick Grayson is an only child. Dick witnesses the owner of the circus, arguing with a crook who is trying to shake him down for protection money. Later on, the same crook disguises himself as a roustabout and secretly severs one of the ropes on the trapeze. Right before the big Wayne Charities benefit performance, sponsored by a surprisingly unaccompanied Bruce Wayne, Dick recognizes the disguised crook as he leaves the main tent. He tries to tell his parents, but the Flying Graysons act is starting. As the show progresses, the weakened rope grows more frayed with each swing, unnoticed by anyone.

Dick returns to the raised platform while his parent perform their part of the act. As his mother prepares to leap to his father’s waiting arms, Dick finally sees that the trapeze rope is near breaking. He calls out to his father, but it’s too late.

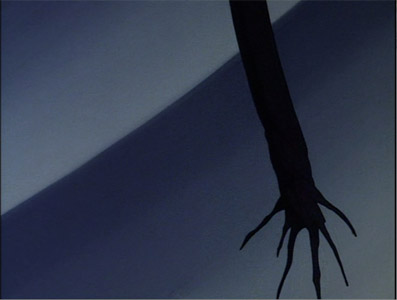

The camera catches part of Mrs. Grayson’s jump, but mainly follows the couple’s shadows cast by the spotlight on the side of the tent. The shot continues on past the spotlight and into the shadows for an excruciating moment of total silence. Only the snapped rope swings back, accompanied by a high chord and gasps of horror. The shocked audience is seen only in silhouette except for one figure: Bruce Wayne.

What can we learn in comparing these two scenes? We can see what elements are crucial to the origin of Robin. Dick Grayson’s parents have to be killed to drawn a connection between Dick and fellow orphan Bruce Wayne and leave Dick in need of a family. Dick’s circus acrobat past is also essential in providing Dick with the skills to be a capable sidekick for Batman. And Bruce Wayne is always there when it happens, giving him all the more reason to get personally involved in Dick's future.

Strangely, it’s the live action film that is the more colorful and gaudy of the two, typical of the visual spectacle in this era of Batman movies. The circus in the animated series is much darker and more reserved in design. The earlier Batman films tended to focus heavily on Batman's impressive rogues gallery, often to the exclusion of less flashy foes. So small time criminal Tony Zucco is out and Two-Face is in.

It’s tempting to conclude that animation is better than live action, but I don’t think the comparison between a mediocre to bad movie and a top quality television series is a fair one. However, if you want to conclude that superheroes generally work better in animation than they do in live action, I’m not going to stop you.

One of the big conclusions that I come to when watching these two scenes is that less is more, especially when it comes to scenes about fear or horror. What isn’t shown is often far more terrifying than what is. Batman Forever is particularly gory. It has its own limitations to deal with and can't be too graphic for younger members of the audience. The actual impact is never shown, there’s no blood, and the emotion of the scene is carried largely by the characters’ reactions. But we do see the Graysons’ fall, their dead bodies, and Dick’s immediate reaction to discovering that his family has been murdered. And yet, the whole scene is not nearly as effective as the one from Batman: TAS. Since there’s only just enough on-screen to indicate what happened, it is left to the viewer to imagine the Graysons’ fall and the expression of Dick’s face as he watches his parents plummet to their deaths. Whatever specific or vague images the viewers may conjure up their minds are almost certainly more frightening than anything that the animators and story artists could have drawn, or anything they would have been allowed to draw,.

Even though the decision to keep the Graysons’ deaths offscreen ultimately works, it wasn’t made purely for artistic reasons. As show writer and co-producer Paul Dini notes in Batman Animated, the network censors would not have allowed the Graysons to die onscreen. For all its darkness and maturity, Batman: TAS was still required to be appropriate for the young viewers who were expected to make up most of its audience. Even the relatively tame version that we see in Batman Forever would have been too much. So director Dick Sebast and his crew had to come up with something that would satisfy the network and still make it clear that Dick Grayson’s parents were dead.

Had the show’s creators been given the freedom to stage the scene however they wanted, the finished product could have been the exact same scene, a scene closer to the one in Batman Forever, or something completely different. It’s impossible to say whether the scene would have been better or worse, but looking at how a PG-13 movie with fewer content restrictions handled the death of the Graysons, I feel like the limitations placed on Batman: TAS were actually helpful in this case.

Any kind of animation – or any kind of creative work – has limitations. Even the most permissive of networks or studios is going to insist that the finished product fit into a particular timeframe, meet a specified budget and deadline, and appeal to a certain demographic. Independent animators are not free of limitations. They too must contend with the limitations of budget, the medium itself, and their own abilities. A solo animator working on a personal project can only devote so much time and resources to a project that may never even pay for itself. Limitations are inescapable. But the right limitations used in the right way can be quite useful.

What limitations can do is to force artists to think about their work in a different way. Even great artists can sometimes find themselves falling back on the same set of ideas over and over again. Limitations can put artists into problem solving mode: “How do I turn this uninspiring project I’ve been handed into something good?” “How do I show violence without gore?” “How do I use the time and money I have to make the best animation I can?”

Working within limitation can sometimes produce results that are far more interesting and unique than if the artist had been given total creative freedom. Limitations can also help artists to focus their efforts on what’s most important about the projects they’re working on. An animator working with no fixed deadline, no guidelines, and an unlimited budget could easily go through endless revisions of a constantly changing project. An animator who has time, money, and content restrictions is more likely to figure out where and how that time and money is best spent to make the project shine.

Do limitations always help? No. Though they can be useful, there are plenty of ways in which limitations can squash creativity to. Going back to Batman: TAS, at least one idea for an episode was scrapped because of a mandate from the higher-ups late in the show’s run that Robin had to be in every episode. This meant either shoehorn Robin into a story that didn't need him or ditching the idea entirely.

There are all kind of limitations that are imposed for bad reasons: the desire to promote a related product, limited or dated views of what kids will and won’t like, overreaction to a current event that will be long past by the time the episode airs, and so on. Limitations based on knee-jerk reactions or stereotypical views of what animation can or cannot do are seldom helpful. Neither are limitations that harm the core concept of the project, like putting extreme limitations on the kind of conflict and behavior the heroes can engage in.

Limitations aren’t inherently good or bad. Too many limitations can stifle creativity. But the ideal of no limitations does not automatically lead to a masterpiece, assuming such an ideal is even attainable. The successful artist is not the one who seeks total freedom from limitations, but the one who seeks to understand the limitations on the project, fights the unreasonable ones that do harm to the core concept, and tries out different ideas to work within the rest. The result may not be exactly what would have ended up onscreen if the limitations had not been there. But sometimes, because the creators had to try different methods for communicating their ideas, it may be better.

* My dad’s term for the ladies who formed a relationship with Batman. The numerous ladies who Bruce Wayne sated in order to keep up his wealthy playboy façade were dismissed as “Bruce’s bimbos.”